Can the company that made this motorcycle in 1921 teach you anything about media relations in this age of media fragmentation?

Lately most of my work falls into one of two buckets: motorcycle journalism or corporate communications in the tech world. Last week, Italy’s Piaggio Group celebrated the 100th birthday of its Moto Guzzi brand. The way Piaggio handled the centenary provide an interesting lesson – and not just for motorcycle companies but in comms generally.

Moto Guzzi was incorporated on March 15, 1921. The normal PR approach would be to craft a tight press release, curate a few photos and try to control the story.

Piaggio indeed wrote a press release that skimmed the storied brands highlights. But then it sent journalists like me a link to a WeTransfer site with scores of historic photo, and video b-roll. Basically it invited journalists to find their own angles.

Of course some lazy web sites just regurgitated the press release and randomly grabbed a few photos. But the document dump enabled more enterprising writers to take a much deeper diver into Moto Guzzi history. They wrote more engaging, stickier stories.

Imagine my surprise when I opened the zip file and saw over a dozen directories, many of which had subdirectories. There are hundreds of files in here.

I don’t know whether the decision to provide so much material – far, far more than journalists would usually get – was thought out or whether in the day-to-day chaos and COVID someone at Piaggio was just too rushed to curate photos and gave us all of them.

If it was thought out it was a stroke of genius. If the latter, it was a lucky accident other companies can learn from. Here’s why…

In the old days, PR around an event like the Moto Guzzi centenary would have been directed to a handful of big motorcycle magazines. Having Cycle World (which for a long time was the largest-circulation motorcycle rag) run the press release verbatim would be a PR win.

But Cycle World’s once-huge audience of enthusiasts is now fragmented amongst many, many web sites and blogs. People that would have read the magazine cover-to-cover once a month now skip across several websites while sipping their morning coffee. If those people see the same press release regurgitated or even hastily re-written, they’ll just think, “Oh I’ve already read this,” and scroll to the next story.

By giving up control of the narrative, Piaggio encouraged journalists to write a bunch of different stories, about whatever caught their eye in that massive document drop. The result was more – and more engaging – stories.

No matter what business you’re in, it’s tempting to try to control your narrative. I work with clients to help them frame stories for other journalists. But sometimes you should step back and admit that writers and editors probably know their audiences better than you do. Even if a journalist resists or ignores your story framing, rest assured they’ll always write a better story about something they find interesting.

Next time, try giving journalists more latitude.

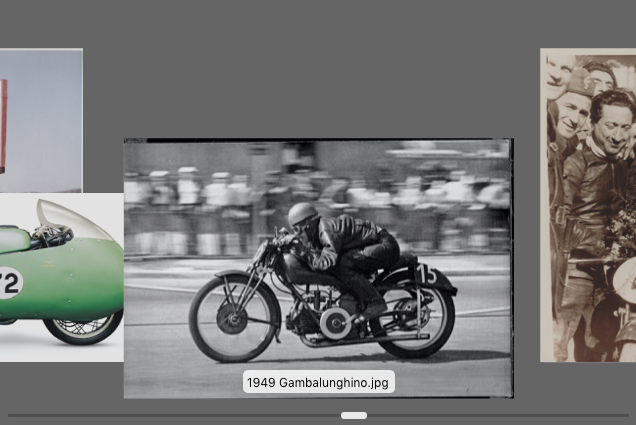

At tip though: Piaggio provided almost no captioning information, except for dates and (usually) model names — in this case “Gambalughino” refers to this 250cc production racer. This jpg was also in another file, in which the rider was identified but the year and machine were not. As a journalist, I love getting good photos that I can pass on to my editors, but I know they’ll ask, “Who, What, When, Where, and Why is this important?” Next time, help a bit-stained wretch out with the information needed to write informative captions.